- Home

- Lisa McMann

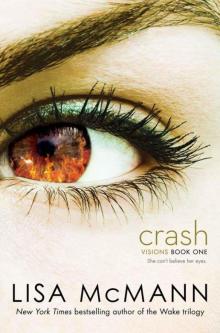

Crash

Crash Read online

* * *

Thank you for downloading this eBook.

Find out about free book giveaways, exclusive content, and amazing sweepstakes! Plus get updates on your favorite books, authors, and more when you join the Simon & Schuster Teen mailing list.

CLICK HERE TO LEARN MORE

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com/teen

* * *

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

About Lisa McMann

One

My sophomore psych teacher, Mr. Polselli, says knowledge is crucial to understanding the workings of the human brain, but I swear to dog, I don’t want any more knowledge about this.

Every few days I see it. Sometimes it’s just a picture, like on that billboard we pass on the way to school. And other times it’s moving, like on a screen. A careening truck hits a building and explodes. Then nine body bags in the snow.

It’s like a movie trailer with no sound, no credits. And nobody sees it but me.

• • •

Some days after psych class I hang around by the door of Mr. Polselli’s room for a minute, thinking that if I have a mental illness, he’s the one who’ll be able to tell me. But every time I almost mention it, it sounds too weird to say. So, uh, Mr. Polselli, when other people see the “turn off your cell phones” screen in the movie theater, I see an extra five-second movie trailer. Er . . . and did I mention I see stills of it on the billboard by my house? You see Jose Cuervo, I see a truck hitting a building and everything exploding. Is that normal?

The first time was in the theater on the one holiday that our parents don’t make us work—Christmas Day. I poked my younger sister, Rowan. “Did you see that?”

She did this eyebrow thing that basically says she thinks I’m an idiot. “See what?”

“The explosion,” I said softly.

“You’re on drugs.” Rowan turned to our older brother, Trey, and said, “Jules is on drugs.”

Trey leaned over Rowan to look at me. “Don’t do drugs,” he said seriously. “Our family has enough problems.”

I rolled my eyes and sat back in my seat as the real movie trailers started. “No kidding,” I muttered. And I reasoned with myself. The day before I’d almost been robbed while doing a pizza delivery. Maybe I was still traumatized.

I just wanted to forget about it all.

But then on MLK Day this stupid vision thing decided to get personal.

Two

Five reasons why I, Jules Demarco, am shunned:

1. I smell like pizza

2. My parents make us drive a meatball-topped food truck to school for advertising

3. I haven’t invited a friend over since second grade

4. Did I mention I smell like pizza? Like, its umami*-ness oozes from my pores

5. Everybody at school likes Sawyer Angotti’s family’s restaurant better

Frankly, I don’t blame them. I’d shun me too.

Every January my mother says Martin Luther King Jr. weekend gives us the boost we need to pay the rent after the first two dead weeks of the year. She’s superpositive about everything. It’s like she forgets that every month is the same. Her attitude is probably what keeps our business alive. But if my mother, Paula, is the backbone of Demarco’s Pizzeria, my father, Antonio, is the broken leg that keeps us struggling to catch up.

There’s no school on MLK Day, so Trey and I are manning the meatball truck in downtown Chicago, and Rowan is working front of house in the restaurant for the lunch shift. She’s jealous. But Trey and I are the oldest, so we get to decide.

The food truck is actually kind of a blast, even if it does have two giant balls on top, with endless jokes to be made. Trey and I have been cooking together since we were little—he’s only sixteen months older than me. He’s a senior. He’s supposed to be the one driving the food truck to school because he has his truck license now, but he pays me ten bucks a week to secretly drive it so he can bum a ride from our neighbor Carter. Carter is kind of a douche, but at least his piece-of-crap Buick doesn’t have a sack on its roof.

Trey drives now and we pass the billboard again.

“Hey—what was on the billboard?” I ask as nonchalantly as I can.

Trey narrows his eyes and glances at me. “Same as always. Jose Cuervo. Why?”

“Oh.” I shrug like it’s no big deal. “Out of the corner of my eye I thought it had changed to something new for once.” Weak answer, but he accepts it. To me, the billboard is a still picture of the explosion. I look away and rub my temples as if it will make me see what everybody else sees, but it does nothing. Instead, I try to forget by focusing on my phone. I start posting all over the Internet where Demarco’s Food Truck is going to be today. I’m sure some of our regulars will show up. It’s becoming a sport, like storm chasing. Only they’re giant meatball chasing.

Some people need a life. Including me.

We roll past Angotti’s Trattoria on the way into the city—that’s Sawyer’s family’s restaurant. Sawyer is working today too. He’s outside sweeping the snow from their sidewalk. I beg for the traffic light to stay green so we can breeze past unnoticed, but it turns yellow and Trey slows the vehicle. “You could’ve made it,” I mutter.

Trey looks at me while we sit. “What’s your rush?”

I glance out the window at Sawyer, who either hasn’t noticed our obnoxious food truck or is choosing to ignore it.

Trey follows my glance. “Oh,” he says. “The enemy. Let’s wave!”

I shrink down and pull my hat halfway over my eyes. “Just . . . hurry,” I say, even though there’s nothing Trey can do. Sawyer turns around to pick up a bag of rock salt for the ice, and I can tell he catches sight of our truck. His head turns slightly so he can spy on who’s driving, and then he frowns.

Trey nods coolly at Sawyer when their eyes meet, and then he faces forward as the light finally changes to green. “Do you still like him?” he asks.

Here’s me, sunk down in the seat like a total loser, trying to hide, breathing a sigh of relief when we start rolling again. “Yeah,” I say, totally miserable. “Do you?”

Three

Trey smiles. “Nah. That urban underground thing he’s got going on is nice, and of course I’m fond of the, ah, Mediterranean complexion, but I’ve been over him for a while. He’s too young for me. You can have him.”

I laugh. “Yeah, right. Dad will love that. Maybe me hooking up with an Angotti will be the thing that puts him over the edge.” I don’t mention that Sawyer won’t even look at me these days, so the chance of me “having”

Sawyer is zero.

Sawyer Angotti is not the kind of guy most people would say is hot, but Trey and I have the same taste in men, which is sometimes convenient and sometimes a pain in the ass. Sawyer has this street casual look where he could totally be a clothes model, but if he ever told people he was one, they’d be like, “Seriously? No way.” Because his most attractive features are so subtle, you know? At first glance he’s really ordinary, but if you study him . . . big sigh. His vulnerable smile is what gets me—not the charming one he uses on teachers and girls and probably customers, too. I mean the warm, crooked smile that doesn’t come out unless he’s feeling shy or self-conscious. That one makes my stomach flip. Because for the most part, he’s tough-guy metro, if such a thing exists. Arms crossed and eyebrow raised, constantly questioning the world. But I’ve seen his other side a million times. I’ve been in love with him since we played plastic cheetahs and bears together at indoor recess in first grade.

How was I supposed to know back then that Sawyer was the enemy? I didn’t even know his last name. And I didn’t know about the family rivalry. But the way my father interrogated me after they went to my first parent-teacher conference and found out that I “played well with others” and “had a nice friend in Sawyer Angotti,” you’d have thought I’d given away great-grandfather’s last weapon to the enemy. Trey says that was right around the time Dad really started acting weird.

All I knew was that I wasn’t allowed to play cheetahs and bears with Sawyer anymore. I wasn’t even supposed to talk to him.

But I still did, and he still did, and we would meet under the slide and trade suckers from the candy jar each of our restaurants had by the cash register. I would bring him grape, and he always brought me butterscotch, which we never had in our restaurant. I’d do anything to get Sawyer Angotti to give me a butterscotch sucker again.

I have a notebook from sixth grade that has nine pages filled with embarrassing and overdramatic phrases like “I pine for Sawyer Angotti” and “JuleSawyer forever.” I even made an S logo for our conjoined names in that one. Too bad it looks more like a cross between a dollar sign and an ampersand. I’d dream about us getting secretly married and never telling our parents.

And back then I’d moon around in my room after Rowan was asleep, pretending my pillow was Sawyer. Me and my Sawyer pillow would lie down on my bed, facing one another, and I’d imagine us in Bulger Park on a blanket, ignoring the tree frogs and pigeons and little crying kids. I’d touch his cheek and push his hair back, and he’d look at me with his gorgeous green eyes and that crooked, shy grin of his, and then he’d lean toward me and we’d both hold our breath without realizing it, and his lips would touch mine, and then . . . He’d be my first kiss, which I’d never forget. And no matter how much our parents tried to keep us apart, he’d never break my heart.

Oh, sigh.

But then, on the day before seventh grade started, when it was time to visit school to check out classes and get our books, his father was there with him, and my father was there with me, and I did something terrible.

Without thinking, I smiled and waved at my friend, and he smiled back, and I bit my lip because of love and delight after not seeing him for the whole summer . . . and his father saw me. He frowned, looked up at my father, scowled, and then grabbed Sawyer’s arm and pulled him away, giving my father one last heated glance. My father grumbled all the way home, issuing half-sentence threats under his breath.

And that was the end of that.

I don’t know what his father said or did to him that day, but by the next day, Sawyer Angotti was no longer my friend. Whoever said seventh grade is the worst year of your life was right. Sawyer turned our friendship off like a faucet, but I can’t help it—my faucet of love has a really bad leak.

• • •

Trey parks the truck as close to the Field Museum as our permit allows, figuring since the weather is actually sunny and not too freezing and windy, people might prefer to grab a quick meal from a food truck instead of eating the overpriced generic stuff inside the tourist trap.

Before we open the window for business, we set up. Trey checks the meat sauce while I grate fresh mozzarella into tiny, easily meltable nubs. It’s a simple operation—our winter truck specialty is an Italian bread bowl with spicy mini meatballs, sauce, and cheese. The truth is it’s delicious, even though I’m sick to death of them.

We also serve our pizza by the slice, and we’re talking deep-dish Chicago-style, not that thin crap that Angotti’s serves. Authentic, authschmentic. The tourists want the hearty, crusty, saucy stuff with slices of sausage the diameter of my bicep and bubbling cheese that stretches the length of your forearm. That’s what we’ve got, and it’s amazing.

Oh, but the Angotti’s sauce . . . I had it once, even though in our house it’s contraband. Their sauce will lay you flat, seriously. It’s that good. We even have the recipe, apparently, but we can’t use it because it’s patented and they sell it by the jar—it’s in all the local stores and some regional ones now too. My dad about had an aneurysm when that happened. Because, according to Dad, in one of his mumble-grumble fits, the Angottis had been after our recipe for generations and somehow managed to steal it from us.

So I guess that’s how the whole rivalry started. From what I understand, and from what I know about Sawyer avoiding me like the plague, his parents feel the same way about us as my parents feel about them.

• • •

Trey and I pull off a really decent day of sales for the middle of January. We hightail it back home for the dinner rush so we can help Rowan out.

As we get close, we pass the billboard from the other side. I locate it in my side mirror, and it’s the same as this morning. Explosion. I watch it grow small and disappear, and then close my eyes, wondering what the hell is wrong with me.

• • •

We pull into the alley and park the truck, take the stuff inside.

“Get your asses out there!” Rowan hisses as she flies through the kitchen. She gets a little anxious when people have to wait ten seconds. That kid is extremely well put together, but she carries the responsibility of practically the whole country on her shoulders.

Mom is rolling out dough. I give her a kiss on the cheek and shake the bank bag in her face to show her I’m on the way to putting it in the safe like I’m supposed to. “Pretty good day. Had a busload of twenty-four,” I say.

“Fabulous!” Mom says, way too perky. She grabs a tasting utensil, reaches into a nearby pot, and forks a meatball for me. I let her shove it into my mouth when I pass her again.

“I’s goo’!” I say. And really freaking hot. It burns the roof of my mouth before I can shift it between my teeth to let it cool.

Tony, the cook who has been working for our family restaurant for something like forty million years, smiles at me. “Nice work today, Julia,” he says. Tony is one of the few people I allow to call me by my birth name.

I guess my dad, Antonio, was actually named after Tony. Tony and my grandfather came to America together. I don’t really remember my grandpa much—he killed himself when I was little. Depression. A couple of years ago I accidentally found out it was suicide when I overheard Mom and Aunt Mary talking about it.

When I asked my mom about it later, she didn’t deny it—instead, she said, “But you kids don’t have any sign of depression in you, so don’t worry. You’re all fine.” Which was about the best way to make me think I’m doomed.

It’s a weird thing to find out about your family, you know? It made me feel really different for the rest of the day, and it still does now whenever I think about it. Like we’re all wondering where the depression poison will hit next, and we’re all looking at my dad. I wonder if that’s why my mother is so upbeat all the time. Maybe she thinks she can protect us with her happy shield.

Trey and I hurry to wash up, grab fresh aprons, and check in with Aunt Mary at the hostess stand. She’s seating somebody, so we take a look at the chart and s

ee that the house is pretty full. No wonder Rowan’s freaking out.

Rowan’s fifteen and a freshman. Just as Trey is sixteen months older than me, she’s sixteen months younger. I don’t know if my parents planned it, and I don’t want to know, but there it is. I pretty much think they had us for the sole purpose of working for the family business. We started washing dishes and busing tables years ago. I’m not sure if it was legal, but it was definitely tradition.

Rowan looks relieved to see us. She’s got the place under control, as usual. “Hey, baby! Go take a break,” I whisper to her in passing.

“Nah, I’m good. I’ll finish out my tables,” she says. I glance at the clock. Technically, Rowan is supposed to quit at seven, because she’s not sixteen yet—she can only work late in the summer—but, well, tradition trumps rules sometimes. Not that my parents are slave drivers or anything. They’re not. This is just their life, and it’s all they know.

• • •

It’s a busy night because of the holiday. Busy is good. Busy means we can pay the rent, and whatever else comes up. Something always does.

By ten thirty all the customers have left. Even though Dad hasn’t come down at all this evening to help out, Mom says she and Tony can handle closing up alone, and she sends Trey and me upstairs to the apartment to get some sleep.

I don’t want to go up there.

Neither does Trey.

Four

Trey and I go out the back and into the door to the stairs leading up to our home above the restaurant. We pick our way up the stairs, through the narrow aisle that isn’t piled with stuff. At the top, we push against the door and squeeze through the space.

Rowan has already done what she could with the kitchen. The sink is empty, the counters are clean. The kitchen is the one sacred spot, the one room where Mom won’t take any garbage from anybody—literally. Because even after cooking all day, she still likes to be able to cook at home too, without having to worry that Dad’s precious stacks of papers are going to combust and set the whole building on fire because they’re too close to the gas stove.

Wake

Wake Dragon Captives

Dragon Captives Project Chimera

Project Chimera Fade

Fade Island of Graves

Island of Graves The Unwanteds

The Unwanteds Gone

Gone Island of Silence

Island of Silence Island of Legends

Island of Legends Dragon Fire

Dragon Fire Going Wild

Going Wild Cryer's Cross

Cryer's Cross Gasp

Gasp Island of Dragons

Island of Dragons Dragon Curse

Dragon Curse The Trap Door

The Trap Door Bang

Bang Dragon Bones

Dragon Bones Dragon Slayers

Dragon Slayers Island of Shipwrecks

Island of Shipwrecks Island of Fire

Island of Fire Dead to You

Dead to You Crash

Crash Island of Silence (Unwanteds)

Island of Silence (Unwanteds) Cryer's Cross (Multimedia eBook Edition with Video)

Cryer's Cross (Multimedia eBook Edition with Video) Going Wild #3

Going Wild #3 Gasp (Visions)

Gasp (Visions) Crash (Visions (Simon Pulse))

Crash (Visions (Simon Pulse))